Semigroup with involution

In mathematics, in semigroup theory, an involution in a semigroup is a transformation of the semigroup which is its own inverse and which is an anti-automorphism of the semigroup. A semigroup in which an involution is defined is called a semigroup with involution or a *– semigroup. In the multiplicative semigroup of real square matrices of order n, the map which sends a matrix to its transpose is an involution. In the free semigroup generated by a nonempty set the operation which reverses the order of the letters in a word is an involution.

Contents |

Formal definition

Let S be a semigroup. An involution in S is a unary operation * on S (or, a transformation * : S → S, x → x*) satisfying the following conditions:

- For all x in S, (x*)* = x.

- For all x, y in S we have ( xy )* = y*x*.

The semigroup S with the involution * is called a semigroup with involution.

Examples

- If S is a commutative semigroup then the identity map of S is an involution.

- If S is a group then the inversion map * : S → S defined by x* = x−1 is an involution.

- If S is an inverse semigroup then the inversion map is an involution which leaves the idempotents invariant. The inversion map is not necessarily the only map with this property in an inverse semigroup; there may well be other involutions that leave all idempotents invariant. A regular semigroup is an inverse semigroup if and only if it admits an involution under which each idempotent is an invariant.[1]

- Underlying every C*-algebra is a *-semigroup. An important instance is the algebra Mn(C) of n-by-n matrices over C .

- If X is a set, the set of all binary relations on X is a *-semigroup with the * given by the inverse relation, and the multiplication given by the usual composition of relations.

Basic concepts and properties

Certain basic concepts may be defined on *-semigroups in a way that parallels the notions stemming from a (von Neumann) regular element in a semigroup. A partial isometry is an element s when ss*s = s; the set of partial isometries is usually abbreviated PI(S). A projection is an idempotent element e that is fixed by the involution, i.e. ee = e and e* = e. Every projection is a partial isometry, and for every partial isometry s, s*s and ss* are projections. If e and f are projections, then e = ef if and only if e = fe.

Partial isometries can be partially ordered by s ≤ t if and only if s = ss*t and ss* = ss*tt*. Equivalently, s ≤ t if and only if s = et and e = ett* for some projection e. In a *-semigroup, PI(S) is an ordered groupoid with the partial product given by s•t = st if s*s = tt*.

The partial isometries in a C*-algebra are exactly those defined in this section. In the case of Mn(C) more can be said. If E and F are projections, then E ≤ F if and only if imE ⊆ imF. For any two projection, if E ∩ F = V, then the unique projection J with image V and kernel the orthogonal complement of V is the meet of E and F. Since projections form a meet-semilattice, the partial isometries on Mn(C) form an inverse semigroup with the product  .[2]

.[2]

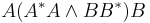

* – regular semigroups

A semigroup S with an involution * is called a * – regular semigroup if for every x in S, x* is H-equivalent to some inverse of x, where H is the Green’s relation H. This defining property can be formulated in several equivalent ways. Another is to say that every L-class contains a projection. An axiomatic definition is the condition that for every x in S there exists an element x’ such that x’xx’ = x’, xx’x = x, ( xx’ )* = xx’, ( x’x )* = x’x. Michael P. Drazin first proved that given x, the element x’ satisfying these axioms is unique. It is called the Moore–Penrose inverse of x. This agrees with the classical definition of the Moore–Penrose inverse of a square matrix. In the multiplicative semigroup Mn ( C ) of square matrices of order n, the map which assigns a matrix A to its Hermitian conjugate A* is an involution. The semigroup Mn ( C ) is a * – regular semigroup with this involution. The Moore–Penrose inverse of A in this * – regular semigroup is the classical Moore–Penrose inverse of A.

P-systems

An interesting question is to characterize when a regular semigroup is a *-regular semigroup. The following characterization was given by M. Yamada. Define a P-system F(S) as subset of the idempotents of S, denoted as usual by E(S). Using the usual notation V(a) for the inverses of a, F(S) needs to satisfy the following axioms:

- For any a in S, there exists a unique a° in V(a) such that aa° and a°a are in F(S)

- For any a in S, and b in F(S), a°ba is in F(S), where ° is the well-defined operation from the previous axiom

- For any a, b in F(S), ab is in E(S); note: not necessarily in F(S)

A regular semigroup S is a *-regular semigroup, as defined by Nordahl & Scheiblich, if and only if it has a p-system F(S). In this case F(S) is the set of projections of S with respect to the operation ° defined by F(S). In an inverse semigroup the entire semilattice of idempotents is a p-system. Also, if a regular semigroup S has a p-system that is multiplicatively closed (i.e. subsemigroup), then S is an inverse semigroup. Thus, a p-system may be regarded as a generalization of the semilattice of idempotents of an inverse semigroup.

Free semigroup with involution

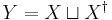

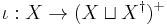

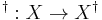

Let  be two disjoint sets in bijective correspondence given by the map

be two disjoint sets in bijective correspondence given by the map

.

.

Denote by (here we use  instead of

instead of  to remind that the union is actually a disjoint union)

to remind that the union is actually a disjoint union)

and by  the free semigroup on

the free semigroup on  . We can extend the map

. We can extend the map  to a map

to a map

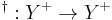

in the following way: given

for some letters

for some letters

then we define

This map is an involution on the semigroup  . This is the only way to extend the map

. This is the only way to extend the map  from

from  to

to  , to an involution on

, to an involution on  .

.

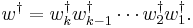

Thus, the semigroup  with the map

with the map  is a semigroup with involution. Moreover, it is the free semigroup with involution on

is a semigroup with involution. Moreover, it is the free semigroup with involution on  in the sense that it solves the following universal problem: given a semigroup with involution

in the sense that it solves the following universal problem: given a semigroup with involution  and a map

and a map

,

,

a semigroup homomorphism

exists such that

where

is the inclusion map and composition of functions is taken in the diagram order. It is well known from universal algebra that  is unique up to isomorphisms.

is unique up to isomorphisms.

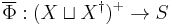

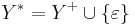

If we use  instead of

instead of  , where

, where

where  is the empty word (the identity of the monoid

is the empty word (the identity of the monoid  ), we obtain a monoid with involution

), we obtain a monoid with involution  that is the free monoid with involution on

that is the free monoid with involution on  .

.

See also

Notes

References

- Mark V. Lawson (1998). "Inverse semigroups: the theory of partial symmetries". World Scientific ISBN 981-02-3316-7

- D J Foulis (1958). Involution Semigroups, Ph.D. Thesis, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA. Publications of D.J. Foulis (Accessed on 5 May 2009)

- W.D. Munn, Special Involutions, in A.H. Clifford, K.H. Hofmann, M.W. Mislove, Semigroup theory and its applications: proceedings of the 1994 conference commemorating the work of Alfred H. Clifford, Cambridge University Press, 1996, ISBN 0521576695. This is a recent survey article on semigroup with (special) involution

- Drazin, M.P., Regular semigroups with involution, Proc. Symp. on Regular Semigroups (DeKalb, 1979), 29–46

- Nordahl, T.E., and H.E. Scheiblich, Regular * Semigroups, Semigroup Forum, 16(1978), 369–377.

- Miyuki Yamada, P-systems in regular semigroups, Semigroup Forum, 24(1), December 1982, pp. 173–187

- This article incorporates material from Free semigroup with involution on PlanetMath, which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License.